The Bayesian Thinking - III

Friday, June 22, 20184 mins read

Read the first part The Bayesian Thinking - I and the second part The Bayesian Thinking - II.

There’s no theorem like Bayes’ theorem

Like no theorem we know

Everything about it is appealing

Everything about it is a wow

Let out all that a priori feeling

You’ve been concealing right up to now!

— George Box

In this post, we’ll do probabilistic programming in PyMC31, a python library for programming Bayesian analysis. We’ll discuss the Bayesian view of linear regression.

Frequentist Linear Regression

In Frequentist Linear Regression,

\[\hat{Y} = \hat{β_{0}} + \hatβ_{1}X_{1} + \hatβ_{2}X_{2} + ... + \hatβ_{p}X_{p}\] \[Y = \hat{Y} + \epsilon = β^T X + \epsilon\]we use least squares fitting procedure to estimate regression coefficients \(\beta_{0}, \beta_{1}, \beta_{2}, ..., \beta_{p}\) while minimizing the loss function using residual sum of squares:

\[RSS = \sum_{i=1}^n(y_{i} - \hat{y_i})^2 = \sum_{i=1}^n(y_{i} - β^T x_{i})^2\]We calculate the maximum liklihood estimate of β, the value that is the most probable for X and y.

\[\hat{β} = (X^T X)^{-1} X^T y\]This method of fitting the model parameters is called Ordinary Least Squares (OLS). We obtain a single estimate for the model parameters based on the training data.

Bayesian Linear Regression

In the Bayesian view, the response, y, is not estimated as a single value, but is drawn from a probability distribution.

where \(\sigma\) represents the observation error.

The response, y is generated from a normal (Gaussian) distribution. In Bayesian linear regression, we determine the posterior distribution of model parameters rather than finding a single best value as in frequentist approach. Using the Bayes theorem, the posterior probability of parameters is given by

We include the guess, of what the parameters’ value can be, in our model, unlike the frequentist approach where everything comes from the data. If we don’t have any estimates, we can non-informative priors such as normal distribution.

import pymc3 as pm

import numpy as np

import matplotlib.pyplot as plt

# true parameter values

alpha, sigma = 1, 1

beta = [1, 2.5]

# size of dataset

size = 100

# predictor variable

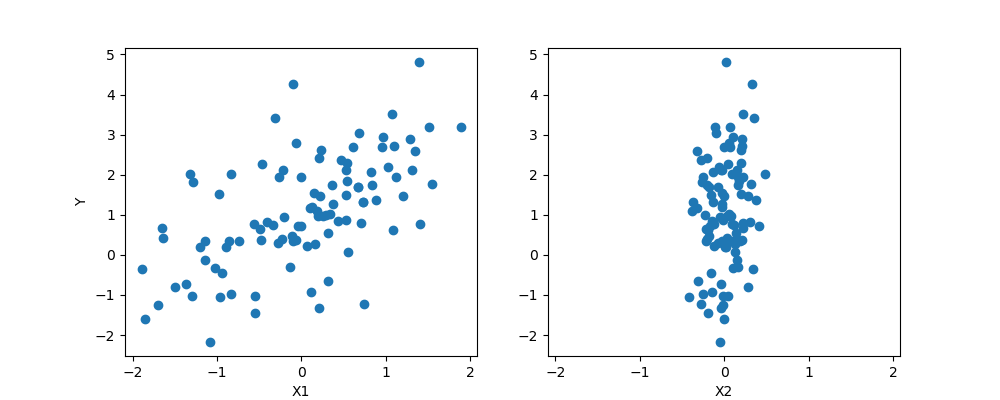

X1 = np.random.randn(size)

X2 = np.random.randn(size) * 0.2

# simulate response variable

Y = alpha + beta[0]*X1 + beta[1]*X2 + np.random.randn(size)*sigma

fig, axes = plt.subplots(1, 2, sharex=True, figsize=(10, 4))

axes[0].scatter(X1, Y)

axes[1].scatter(X2, Y)

axes[0].set_ylabel('Y')

axes[0].set_xlabel('X1')

axes[1].set_xlabel('X2')

# creates new Model object

basic_model = pm.Model()

with basic_model:

# objects introduced here are added to the model behind the scenes

# create stochastic random variables with Normal prior distributions

alpha = pm.Normal('alpha', mu=0, sd=10) # intercept

beta = pm.Normal('beta', mu=0, sd=10, shape=2)

sigma = pm.HalfNormal('sigma', sd=1)

# expected value of response (deterministic random variable)

mu = alpha + beta[0]*X1 + beta[1]*X2

# liklihood (sampling distribution) of observations (responses)

Y_obs = pm.Normal('Y_obs', mu=mu, sd=sigma, observed=Y)

with basic_model:

# draw 500 posterior samples

trace = pm.sample(500)

# posterior analysis

pm.traceplot(trace)Conclusion

The Bayesian reasoning is similar to our natural intuition. We start with an initial estimate, our prior, and as we gather more (data) evidence, we update our beliefs (prior), we update our model.

References: